The Queen's Hair (And Makeup)

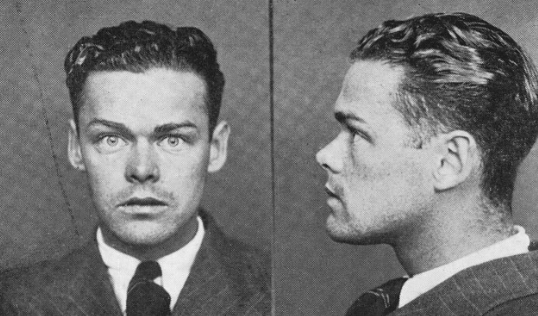

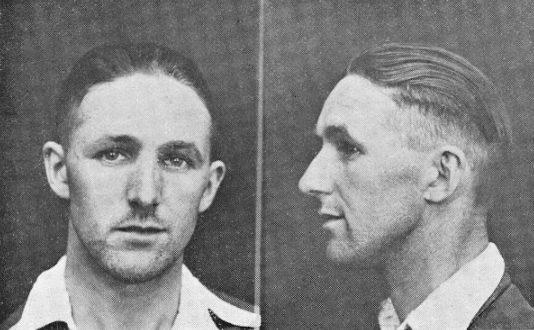

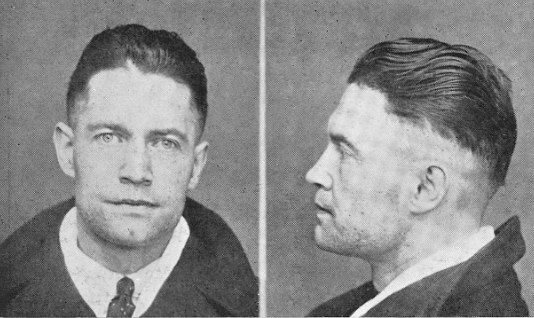

Arthur Ropata Colson Wynyard was a thirty-year-old Auckland music teacher who liked to drive teenagers around town in his three-seater Morris-Cowley; he took a few of them back to his rooms at the Castlebar Private Hotel in Khyber Pass. In 1928, when a youth told a detective about Wynyard’s sexual advances, police escorted Wynyard to the station and photographed him. The resulting images appear in the Police Gazette, and Truth newspaper described his appearance: ‘of medium build, hair jet black and carefully waved [he was] immaculately attired in a light, fashionably cut lounge suit’.

Wynyard’s hair is of a style we saw on the head of Auckland musician Charles Hulton in an earlier post. The finger wave, a relative of the more well-known Marcel wave, was achieved with a combination of fingers, a comb and stiff hair product: wax, perhaps, or Brylcreem which debuted the year Wynyard had his photo taken. Men’s finger wave hairdos were popular among urban queens, several of whom, like Wynyard, found themselves in trouble with the police. The Police Gazette images, along with newspaper reports and published sources, give twenty-first century readers a window into a subcultural style that lasted from the late 1920s until about 1940.

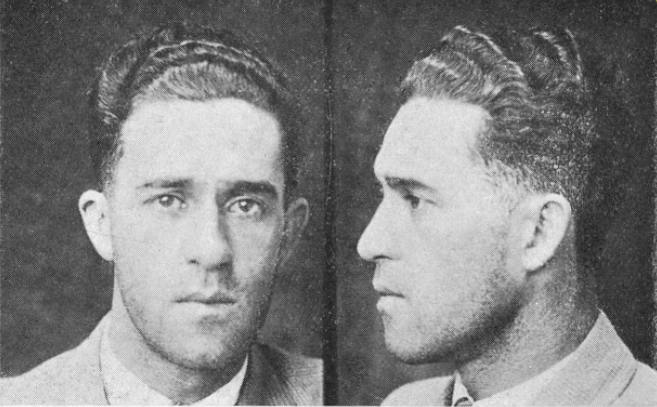

Top: Arthur Ryan; bottom: Thomas Hill.

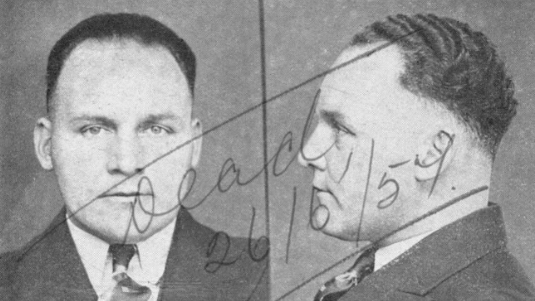

Arthur Ryan and Thomas Millington Hill sported the finger wave style, and both were arrested for having sex with other males – Ryan in Dunedin in 1933 and Hill in Auckland in 1940. Twenty-six-year-old Ryan was a seaman and Hill, thirty-three, a floor walker in a department store. The desecration of his photograph in the Police Gazette reminds us that sometimes, as Susan Sontag puts it, ‘to photograph people is to violate them … it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed’. We see this most profoundly when the authorities forcibly captured a person’s face for the purposes of surveillance – and then crossed it out when declaring him dead.

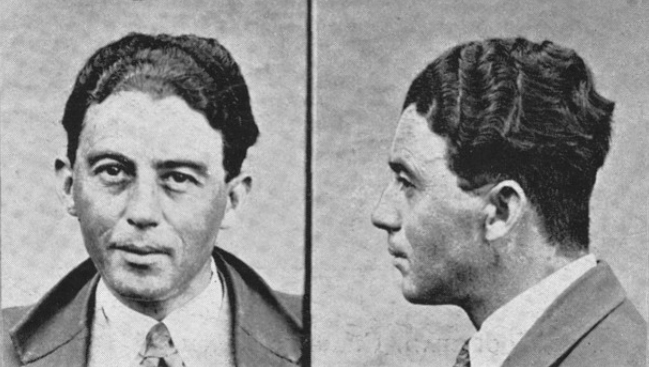

John Gifford Waring Jamison glowered at the camera in 1939 as if unwilling to be possessed by the state. There is the trace of a wave on the fringe of this Auckland waiter and commercial artist, twenty-three years old at the time. Jamison was convicted for buggery, along with his sexual partner, twenty-one-year-old porter John Murphy. Notes in the Police Gazette say Jamison was ‘effeminate’ in appearance, had auburn hair and a ‘snub nose’. He adorned himself with a pencil on his plucked eyebrows, mascara on his lashes, eyeliner on his lids, and perhaps a little powder on his forehead and cheeks. Murphy had naturally curly hair which he swept back off his forehead, and he may have plucked his eyebrows. Arthur Wynyard wore no makeup in his 1928 mugshot even though he owned some: when police inspected his bedroom they discovered ‘a number of toilet articles … seldom found anywhere but on a woman’s dressing-table’, including three powder-puffs and a box of rouge.

Top: John Jamison. Bottom: John Murphy. Following sentencing, the men were split up: Jamison went to New Plymouth Prison and Murphy to Hautu. After his release from prison, Jamison’s life changed markedly: he suspended his work as a commercial artist for a while and served in a light anti-aircraft regiment with the Second New Zealand Expeditionary Force.

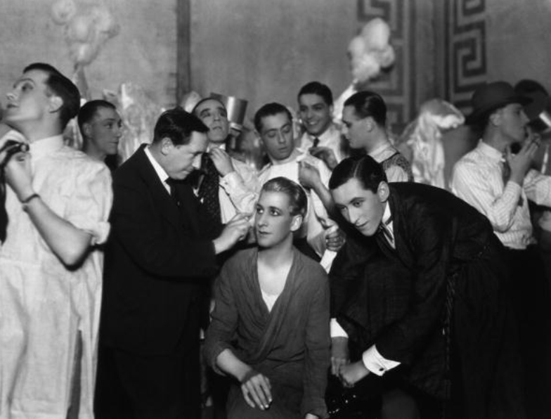

There are also signs of makeup on the face of William Moncrieff Hay, a twenty-seven-year-old fish curer from Australia. He came to police attention one afternoon in 1931, when he made indecent suggestions to a young man at Auckland’s Alexandra Park races. ‘He seemed to be something in the nature of a sexual pervert’, the New Zealand Herald suggested, while a detective declared Hay needed a ‘jolly good hiding’. The judge agreed with the sentiment but fined him £5 instead. Hay did not go in for finger waves: his hair is slicked straight back in a short-sided style not unusual among men at the time. But the combination of brushed back fringe, eyeshadow and plucked eyebrows – he may also have curled his eyelashes – gave Hay the look of an antipodean chorus boy.

Above: William Moncrieff Hay, 1931. Below: Chorus boys behind the scenes of the musical Ever Green at London’s Adelphi Theatre, 1931.

There is no doubt these New Zealand men drew from an international style that signified membership in a homoerotic subculture. In 1931 a journalist for Sydney magazine The Arrow told of a ‘kamp’ party whose guests did themselves up with carmined lips, powder, and Marcel waves or the ‘boyish Eton crop’. The same year, a report about New York ‘pansies’ told of plucked eyebrows, powdered faces, rouged lips and Marcelled hair. British cartoon postcards portrayed effete men with the same finger wave hairstyles as their New Zealand counterparts.

So how did these styles travel into the country? William Hay’s recent arrival from Australia offers one clue, and there are others. New Zealand hosted a remarkable number of visiting entertainers who steamed their way across the seas to perform here, and they may have bought new trends with them. Some locals, including Arthur Ryan, also travelled in and out of our ports. Eric Marshall Walden, a thirty-five-year-old steward on the trans-Tasman steamer Monowai, was arrested in 1936 for sex with another man in Auckland. Walden’s mugshot hairdo owed more to Hay's slicked-back approach than to the finger wave, but his border-crossing occupation hints at the mobility of a look. Maybe, when in Sydney, Hay and Walden went to the same kinds of parties as the Arrow’s reporter, and brought new ideas about hair and fashion back to New Zealand.

Eric Walden in 1936. He went into the Australian Navy after his stint in prison.

The story of queens’ hair tells of the intersections between sexuality, style, urbanity, age and occupation. Not all members of New Zealand’s expanding homoerotic subcultures had finger waves or wore makeup, but some youngish men who worked in the service and creative sectors did just that - especially in rapidly growing Auckland. Most were Pākehā but Wynyard was Māori and Hulton was Tongan. Their look spoke of an identity to themselves and their friends. They may have appeared curious or eccentric to outsiders, often police became suspicious of them, and a few landed in prison. But sometimes their selfhood slid past the state apparatus and is visible to us today.

Noel Hulme and his queer friends in Christchurch during the 1930s, with no finger waves hair in sight – although some men have slicked back hair. Noel reclines against the car, his mate’s arm draped around his shoulder.

Sources

Newspapers: NZ Truth, 26 January 1928; 16 February 1928; NZ Herald, 28 October 1930; 15 February 1940; Auckland Star, 27 October 1930; 25 July 1935; 1 June 1939; Press, 28 October 1932.

Cole, S. (2000) Don We Now Our Gay Apparel: Gay Men's Dress in the Twentieth Century.

Doyle, P. (2005) ‘Public Eye, Private Eye: Sydney Police Mug Shots, 1912-1930’, Scan, 2(3).

Murdoch, W. (2017) Kamp Melbourne in the 1920s and ’30s.

Niles, B. (1931) Strange Brother, pp. 49-50.

Smaal, Y. and Finnane, M. (2019) ‘Flappers and Felons’, in From Sodomy Laws to Same-sex Marriage, p. 83.

Sontag, S. (1979) On Photography, p. 14.

Out History online postcard collection, https://outhistory.org/

New Zealand Police Gazette.